Originally published in Esquire magazine (Russian edition), Oct 2014

https://www.pravilamag.ru/articles/6086-schizophrenia-104/

Summary: Polina Eremenko tells the story of her father, Kolya, a man whose life was shaped by mental illness, alcoholism, and potential misdiagnosis. Through family memories and expert reflections, his early charm and intelligence give way to erratic behavior, hospitalizations, and withdrawal. The story explores the blurred lines between schizophrenia, addiction, and personality disorder, showing how treatment, misjudgment, and family dynamics intersected in his life. Polina captures quiet moments with him, the struggles of understanding, and the eventual numbness of his death, reflecting on the complexity of illness, family, and human fragility.

My father’s dreams

The word Schizophrenia was not used in my family. If someone spoke of my father’s strange behaviors they would say: “Papa doesn’t feel well”. For many years I thought this is an exaggeration: his temperature is fine, he has two legs, two arms. What’s the problem? Yes, he rarely spoke and didn’t show interest in much and was too lazy to get off the couch. Is it really so hard – to get off the couch?

Papa died a year ago. First, I scrupulously restored the facts of his biography. I interviewed my mother and my grandmother. Then I wrote down my own memories. I took all these notes to sociologists and to doctors. I showed these notes to the doctors who treated him and who never saw him; who lived in Russia and who lived thousands of kilometers away; who sees mental patients every day and who prefers to research mental illnesses in a lab.

I wanted very simple answers. When did my father actually get sick? Was it possible to cure him? Was he receiving proper treatment? How was I supposed to behave with him? How were my grandmother and mother supposed to behave with him? Could we really understand him? Could he understand us? Instead of getting answers, I only got new questions. One of them was: did he even have Schizophrenia or had he been misdiagnosed?

Alexander Danilin, Psychiatrist, Moscow Psychoneurological Hospital #23, Russia

The word “Schizophrenia” is almost like the word “Love”. When a person says “I love you”, he could mean anything. For example: “Give me some money” or “Let’s fuck”. This has little to do with love, but we use that one word for everything. Same goes for Schizophrenia. It’s a very abstract definition. There are still no objective methods for diagnosing schizophrenia. When I read the questionnaire filled in by the patient [This is how Schizophrenia is diagnosed], I become somewhat of a judge.

Joel Kleinman, Co-Director of the Molecular Neuropathology Section at the Lieber Institute for Brain Development, USA

You want to know what happens if you get Schizophrenia? So, in the brain you have this region called the Prefrontal cortex. It’s responsible for planning and judging. At one point in time, usually when we reach our teenage years, this cortex starts building connections with other parts of our brain. If something goes wrong here, you get Schizophrenia. Schizophrenia is forever – there is no cure for it. Doctors can help patients manage the so-called “positive symptoms” aka hallucinations, but they cannot restore intellect or the ability to plan and judge.

Here’s a simple test that allows you to identify signs of Schizophrenia. Take three minutes and write down all the animals that come to your mind. Done? A healthy individual will name around 40 animals, an ill person – no more than 24. Here’s why. The first 16 animals come to your mind automatically: cat, dog, horse, monkey… Then you need a strategy. For example: you bring up memories of your last visit to the zoo. Or you start recalling animal groups: fish, birds and so on. If you can come up with any strategy, you’re healthy.

Diana Kachalova, Mother, 54 years old

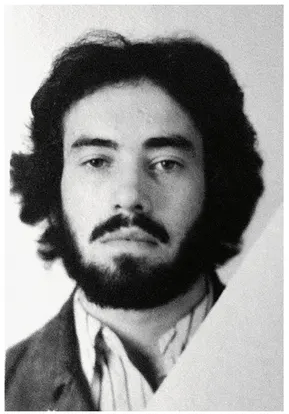

Your father and I met back in 1983 in Crimea in a pub. He was on holiday with his classmates from the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology. It was an incredibly prestigious place to study back then. He looked a bit wild: his hair was curly and crazy, he was wearing faded beige pants with multiple holes. Back then I was into ballet and I had a book about Nijinsky with me. Nijinsky danced with the grace of a cat, a leopard. As we all headed from the bar to the beach, I noticed that this young man, Kolya, moved in such an interesting manner. Like a cat.

When we got to the beach, your father reached the end of the deck, waved to us and jumped in the water with his pants on. He couldn’t care less about the little things. This laid back attitude attracted me. Kolya had a great sense of humor. We laughed all the time. He took life so easy.

We visited each other for a year. I would come to Moscow and he would come to Saint-Petersburg. Your father played in a theater back then and knew theater speculators. It was hard to get tickets for the good shows. Once, he managed to get one ticket for “Master and Margueritte” at the Tagansky Theater. He sent me to the show, while he himself went out for drinks with his friends. When the show was over, no one could share my excitement: they were too drunk.

In November 1983 your father proposed to me. We flew to Volograd to meet his parents. They were happy to meet me. Raisa Semenovna was kind to me. I think she felt sorry for me because my own mother had just passed away. There was one thing that made me tense. Their house was chaos: papers, jars, lids and god knows what else were scattered all over. I only realized they had a piano a year later. With this said, Raisa Semenovna said she will show me some pictures and despite the chaos found them straight away.

Raisa Eremenko, Grandmother 80 years old

I remember meeting your mother. I open the door and there she is. I reach out to hug her. Maybe my manners were too peasant-like? But I can’t help my roots. She took a little step back. I don’t remember if I gave her a hug in the end. Maybe I just chose to pat her on the shoulder instead? That first impression stayed with me.

Mother

The wedding was in Saint Petersburg. A simple wedding. It was hard to reach the Bronze Horseman statue in my sandals in the December snow to get our pictures done, so Kolya carried me in his arms. Relatives came from all over the country. The party was held in my 55-meter room in the communal flat I grew up in. Somebody gifted us with a 2 liter wine glass. Kolya kept filling it up with champagne. He got very drunk and fell asleep in the corner. I felt anger, but I decided to let it go: a drunk husband at the wedding is so banal. The wedding went on for 3 days. It reminded me of a New Year’s celebration that didn’t stop on time: the guests wake up, cure their hangovers with beer and go on partying.

In April 1984 Kolya moved to Saint Petersburg for good. My father found him a job at an instrument making factory. Kolya wanted to work at a research institute, but there were no vacancies. We had a fun life. I tried to live carefree so as to match Kolya. When your sister was born I sewed a kangaroo backpack to carry her around. Back then it was considered wild. Too bad we didn’t have a photo camera.

Grandmother

I came to Saint Petersburg for three months to help with Tanya. I kept noticing that the conversation between your mother and Kolya was not a usual one. I heard her loud voice and didn’t hear Kolya’s voice at all. I spoke to Kolya about this. He said: “Dina yells a bit, it’s true, but then she stops and things are good again”. I told him then: “Dina yells and stops, but the scars on your heart start piling up”.

Mother

Then one day Kolya said we should get rid of the antique parquet and put floor boards instead. We are talking about a parquet that had even the siege of Leningrad [Saint Petersburg] during World War II. Behind the closet he started piling wooden boxes, which he wanted to take apart and polish. The boxes were gradually joined by rusty nails and other construction rubbish. I started growing tense. This mess reminded me of his Volgograd house. I told him if he wants to take off the antique parquet, he’s going to have to kill me first. He chose not to argue and I in return chose to stay cool with his mess. I figured there was enough space for everyone.

Arkady Shmilovich, Head of the Rehabilitation department of the Saint-Petersburg Psychiatric Clinical Hospital #1, Russia

Such interesting tales you tell me about your father. It’s so peculiar for a man with a high intellect to wish to remove such a parquet. It is unfortunate that your mother did not act straight away, when she noticed things were off. It is crucial to run to the doctor when disorders are barely peeking.

Mother

We wanted to move out of our room in the communal flat. So we moved into a 3-room apartment with my two old grandmothers. The grandmothers were happy about the deal, provided they each got a separate room. Kolya, Tanya and I ended up in a small room. Our life was so Soviet there, so overcrowded. You could find privacy in the toilet. We irritated the grannies and they irritated us.

Kolya started to lose his temper. He would say some really cruel things. I started feeling fear: “How can he say that?”. I started feeling like I live with a stranger. He spent his days crafting schemes and reading the Hammer of the Witches. I would calm myself down by saying to myself I’m just picking on the little things. Eventually the clouds left, its was all just a bad dream.

Marieke Pijnenborg, Associate Professor of Clinical Psychology, University of Groningen, Netherlands

For a long time mental disorders were viewed upon in a rigid manner: you either have them or you don’t. Today that attitude has changed. The border between a healthy and ill individual is not so clear. Delirium comes at different intensities and sometimes happens to healthy people too. It can be hard to distinguish normal and pathological behavior.

Mother

Kolya didn’t like working at the instrument making factory. He dreamed of quitting that job. Somebody told him there is an opportunity to go on an expedition to Antarctica. He went for an interview at the Institute of Arctic and Antarctic. They really liked him there. He underwent a number of medical examinations. One of the doctors he saw was a psychiatrist. Kolya was told that he is completely healthy.

It was the deep Autumn of 1987. I was in the hospital, I wasn’t feeling well. You were to be born in a couple of months. The expedition was supposed to take a year. I was sure I would manage. Kolya would visit me at the hospital and promise to bring us a penguin. One day he came and said through the window: “It’s over, they said I can’t go for the expedition”. I never found out what the reason was.

This was the last straw for Kolya. He started drinking even more. His drinking companions started coming to our house. Things were getting darker and darker.

Alexander Danilin

Your father was a weak person. No doubts there. He couldn’t take a hit, he was emotionally unstable, he would get lost in himself. Up until a certain point these issues had simply a neurotic nature. But drinking in order to feel free never brings you to a good place.

Mother

Then our kitchen table broke. It was the 16th of November 1987. Kolya refused to go to the store to get a new one, he said he was busy. I went to the furniture store with Tanya. Everything was in short supply in those years, but I found exactly what I was looking for. A white table with a light blue plastic table top. I called Kolya from the store and asked him to come and pick up the table. Again, he refused. I hung up. I found some guy with a car and asked him to drive us. Kolya was just leaving as we arrived. I was happy to see him, because I thought he would help. Instead he said: “Bring it up on your own, I’m busy”. He left. I brought up the table and assembled it myself. Then I took Tanya and left for my friend’s house. All evening I was complaining to my friend that some kind of darkness had fallen upon Kolya. We stayed over at her house. In the morning my father called and said just one sentence: “Go home immediately”.

It was impossible to open the door. Jars, chairs, furniture: everything was flying at the door. Not a single part of the house was not destroyed. I finally managed to enter the kitchen and discovered the 20-liter jar of homemade wine was almost empty. Kolya was running around and screaming: “I’m going to punish you all!”. It was impossible to calm him down. He went on drinking wine and growing crazier. I found some strong tranquilizers in my grandmother’s medicine box and put them in his wine. Finally, he passed out.

I sat there in the middle of this destroyed house with no idea on how to go on with life. Then I started to clean up. I took the broken glass and broken furniture to the garbage. The light blue plastic top had a crack on it. Somehow, that hurt the most. I didn’t throw it out and we never bought a new table after that. When Kolya woke up he did not apologize for what he did. He just left for a walk.

Dmitry Kolesnikov, Psychiatrist at the Moscow Clinic of Internal Diseases, Russia

Psychiatry is a precise science. I can easily tell you the exact diagnosis of your father: paranoid schizophrenia. The symptoms are right there: delirium and hallucinations. It is important to mention though, that delirium can also occur in a healthy individual if external stimuli are too intense. Say, if you were to put me in the President’s chair for a month, I could also experience paranoia and delirium.

Alexander Danilin

In Russia we like calling everything Schizophrenia. We don’t recognise psychoorganic psychosis or psychosis under the influence of LCD or psychosis as an initial manifestation of hypothyroidism. Nope, we call all of that Schizophrenia. It’s been like this since the 1960’s when Snezhnevskiy, the main psychiatrist of the USSR, came up with the concept of a single psychosis.

Mother

Strange things started happening. Your father installed more locks on the doors. He brought boards to block the balcony door. He covered the windows with rags. He would say he is in trouble. He couldn’t sit in one spot for a long time: he kept disappearing and reappearing. I would call the morgues looking for him. He would return a couple of days later with insane eyes. He didn’t sleep at night, he would move furniture and rearrange dishes. He kept drinking wine, but he never drank as much as that night I had mentioned before.

Bertram Karon, professor in the Psychology department at Michigan State University

People who suffer from Schizophrenia live in a constant state of fear. We can all feel fear once in a while. Sometimes for 5 minutes, sometimes for a whole hour. In this case, fear is you for weeks or months. Usually, it’s the fear of death. Or better put: the fear of non-existence. What thoughts go through the ill man’s mind? He can wind himself up with the fear that somebody is trying to kill them, jump in the first train and disappear. Their hallucinations are their reality.

Mother

I persuaded him to see a psychiatrist. The doctor prescribed some banal pills, Haloperidol I believe. She didn’t make a precise diagnosis. She said it could be Schizophrenia or Bipolar disorder.

Joel Kleinman

Here is the difference between Schizophrenia and Bipolar disorder. Schizophrenia consists of hallucinations and a gradual loss of intellect. Bipolar disorder also consists of hallucinations, but the intellect stays there. People diagnosed with Bipolar disorder become doctors, lawyers, scientists. They get married and have children. How do you diagnose a mental illness correctly? We have the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [DSM-5] for that. A psychiatrist asks the patient questions and then compares the obtained information with criteria in order to make a diagnosis. In the case of Schizophrenia, the psychiatrist is looking for a combination of so-called positive symptoms (hallucinations) and so-called negative symptoms (loss of motivation).

I have some doubts about the accuracy of your father’s diagnosis. Especially, since he was married and had you and your sister. Perhaps, he was misdiagnosed because of his dependency on alcohol. A misdiagnosis and following incorrect treatment can really harm a patient. For instance, prolonged use of Haloperidol is used to treat Schizophrenia, but it’s not a good idea to treat Bipolar disorder with it.

Leonid Ionin, Professor of Sociology at the National Research University Higher School of Economics, Russia

At which point did your father officially become an ill man? After his visit to the psychiatrist.

The first visit to a psychiatrist launches your career as a mentally ill patient. Goethe said: “In our first step we are free, in the second slaves to act”. When this first step has been taken and the person has visited the psychiatrist, he is mentally ill. These social phenomena are very slippery: one step is enough to completely change a man’s biography.

Mother

At the first appointment the psychiatrist asked about bad heredity in the family. I called Raisa Semenovna.

Grandmother

Your grandfather got demobilized from the army in 1965, together with a million others. Just before that he had been to the hospital. His nerves were a little out of order. He spent 10 years in the Air Defense. He would be on duty for days and nights in a row without sleep. Anyone’s nerves would get out of order. I don’t remember the name of his illness.

Joel Kleinman

One’s risk of getting Schizophrenia increases by 10% if there is another relative diagnosed with it. That’s the only information we have about the heredity of this disease. A lot of effort is being put into discovering genes that indicate a higher risk of acquiring Schizophrenia. I, for instance, have spent 36 years looking for this gene. My colleagues and I have collected DNA samples of 38 000 Schizophrenia patients. Right now we don’t have an answer, we are still in the stage of collecting data. We might have an answer in 10 years. Well, at least I’m going to work on getting there every day.

Mother

Your father started taking his medication and in a few months he became absolutely normal again. He got a job at the Institute of Applied Astronomy. He seemed to be enjoying it. You were born. I started thinking that maybe that Autumn nightmare never happened.

Then his boss called me up and asked to meet me. When I came to his office, this boss kept shifting from one foot to the other. He said: “Kolya is behaving strangely. He keeps going somewhere, for some kind of walks. A couple of days ago he brought a fishing rod and rubber boots to work. He goes to the river to catch fish. He’s working on calculations that have nothing to do with work. Do something”.

We persuaded him to stay in the hospital for a bit. It started feeling like he lives behind a tulle curtain. He walked like a normal person and used normal words, but he didn’t seem to understand what was happening around him anymore. “You think I need to go to the hospital? Ok, let’s go”. Sometimes, his condition would improve and he would start arguing. “I’m not going to the hospital anymore, I’m normal”. Time after time he kept ending up in the hospital.

The doctor warned me up front: you will get tired of this soon. I argued: “No, I’m not like that”. She would go on: “That’s just how it is. Usually in such cases the patient ends up living with his mother”. We lived this life for four more years and at one point I understood I can’t be with a man out of pure pity. That’s all there was left. During a work trip to America I met Robert. When I got back I asked Kolya for a divorce. In October 1992, Tanya, you and I left for America.

Grandmother

We came from Volgograd to see you off to America. I didn’t go to the airport, but your grandfather said that Kolya was having a hard time, he was crying. Your mother was his first love and he was brought up to believe that first love lasts forever. I don’t know precisely how much Diana is to blame for his illness and how much genetics are to blame. I can assume that their difficult relationship with Diana aggravated his condition.

Joel Kleinman

I can tell you for sure that your mother is not responsible for your father’s illness. There is no data that would suggest that a wife could induce Schizophrenia in her husband.

Grandmother

When Kolya got back from the airport he broke the entrance door. I called the ambulance. What else could I do? I visited him at the hospital a couple of days later. The doctor said his treatment will take some time. One of the patients in the ward said a nurse stole his golden wedding ring. The next I came, the boys were standing near the window, waiting for visitors. They told me: “Are you here to see Nikolay? He’s not feeling today, he got shots”. Then he was led by the arms of others to the window. He was whispering something to himself, but he couldn’t see me.

I asked what kind of treatment he was receiving. What are these pills and shots? Nobody explained anything to me. Your father, obviously, couldn’t recall that information either. He stayed in the hospital for a month. He left the hospital with a paper that stated he was now officially mentally disabled. We went back home, back to Volgograd.

Alexander Danilin

Could your father have pulled through if he had stayed in Saint Petersburg? Yes. Or he could have died. You can’t stop drinking for the sake of your mother, your wife or your daughter. You can only do it for yourself. That’s why all European (not Russian) textbooks on addiction underline that any kind of therapy for an alcoholic starts with his family refusing to serve his needs. If you want to drink – get the hell out of here, you won’t get any more money here. The person must end up in a situation where he must serve himself. In most cases the majority understand they need to survive somehow, get their act together and start working instead of going on fishing trips during working hours.

Before stuffing all those pills in him, it would’ve been a good idea for a psychologist to talk to him and understand what’s happening. You know, to a certain extent your brain is your father’s brain. But you, thanks to your mother, to yourself, to men learned to understand that your madness is also your talent. Nobody taught him that. He was just given a diagnosis “Schizophrenia” and a pill prescription, end of story.

Grandmother

In a few weeks Kolya came to his senses. I tried to play chess with him, but after he won several times he grew bored. He got a job laying bricks, even despite his disability paper. He worked for a few months and built a kiosk at the Central market. I noticed he wasn’t enjoying the job. He wanted something intellectual. Sometimes he would help me with the embroidery work at home. Back in those years I made embroideries for sale. He liked sewing the part of the pot for the violets. Sometimes he helped at the Young Naturalist center where I worked as a cleaner. But he never got a permanent job after that.

In the early 2000-s he ended up in the hospital again. I would bring the nurses chocolate and once a nurse told me what happens there. Many detainees were hiding in the hospital in order not to serve their sentences in jail. The doctors made use of them: when the patients got violent, the detainees would beat them down. Detainees stole their food, forced them to scrub toilets. Kolya was very soft and did not push back. I decided he’s not going back to the hospital. When he would grow aggressive, I would move into his room. I slept on the sofa and he slept on the floor. Sometimes he would leave home and wander. One time he walked along the Volga river for many hours with our garbage can, until we could finally find him.

Instead of staying in the hospital, he started going to a neuropsychological center once a month for a shot. His doctor’s name was Olga Ivanovna. She would give him Moditen Depo shots [a strong long-acting antipsychotic medication, eliminates uneasiness and irritability, hallucinations and delirium].

Dmitry Kolesnikov

Moditen Depo relieves the patient from symptoms. That’s how your father managed to exist for so many more years with his illness without reaching complete feeble-mindedness.

Joel Kleinman

One of the reasons why your father lost all interest in his life could’ve been Moditen Depo. It’s a really strong tranquilizer. Taking tranquilizers makes it hard to concentrate on anything, even reading a book becomes a huge accomplishment.

Grandmother

He made friends in the center where he received his shots. Volodya and Vitalik. They started coming to our house to drink. I told Kolya he needs to be cautious with vodka, and Volodya told him that alcohol helps battle the illness and if he drinks alcohol he won’t end up in the hospital again. Somewhere in the mid 2000’s Volodya commited suicide by hanging himself after his wife left him. A horrible thing happened to his other friend Vitalik a few years later. He killed his mother during a fit and got sent to jail. We didn’t let Kolya find this out.

Dmitry Kolesnikov

It’s not rare that Schizophrenics drink too much. It’s a type of psychotropic drug for them. It takes away the anxiety and arousal. Was drinking a good idea? I’m not supposed to say this, but I will say it. Yes. An unspoken truth is that with alcohol this illness progresses at a slower pace. With this being said, the side effects of drinking are pretty serious: delirium, cirrhosis, sudden death.

Alexander Danilin

After hearing your story I know I guessed right: this story is about an alcoholic, not a Schizophrenic. A tragic, transparent and very clear story about an alcoholic, whose mind was finally blown away by an extremely toxic medication. You say you can’t understand why he had no emotions left by the end of his life? How about right now I give you a shot of Moditen Depot? Just for the sake of an experiment. And then I’ll watch you try talking about your emotions. You’re going to look like a schizophrenic in less than a week. Most likely your father just had some kind of organic disorder of the nervous system. This is neurology, not psychiatry.

Me

The last years of my father I can recall on my own, not based on the stories of my mother and grandmother. We came back from America 5 years later. Every year up until my father’s death, my sister and I would visit him during our summer vacation. All these years papa to me was a figure smoking on the balcony. He could stand there for hours. In the early years when I visited, I really wanted us to be friends and to play together. I kept nagging him, teasing him, but he didn’t really react to much. He would just smile back. I throw an apricot pit at his head – he smiles. I flush all his cigarettes down the toilet – he smiles. The time we spent together we spent in silence.

I couldn’t understand why he behaved the way he did, but I still loved him. I remember hanging out at our summer house together. I climbed the cherry tree and I told him I’m not going back to Saint Petersburg that Autumn, I’m staying with him for good. He smiled. He never acted like a sick person, more just like a very withdrawn person. I came to the conclusion then that his lack of interest in anything except smoking cigarettes on the balcony comes simply from him being extremely lazy.

Olga Ivanovna, My father’s doctor

Your father’s withdrawal was the result of an emotional-volitional defect. His main problem was not so much his positive symptoms, it was more the fact that he had no will to work, communicate, or read books. He didn’t even want to shower. Your grandmother would sometimes visit me and say: “I feel that Kolya is getting better”. I would carefully explain that with this illness getting better is not possible. The emotional-volitional defect is irreversible. I remember your father well. He was so completely harmless, even though he did sometimes do inadequate things. Once he soaked your grandfather’s fur hats in the bathtub. I asked Kolya why he did it. He said: “I wanted to wash them, they were dirty”. But he didn’t wash them, he just left them floating in the bathtub.

Joel Kleinman

You say that your father seemed lazy to you. But you must understand, there is no such thing as “lazy” in psychiatry. Schizophrenics are not lazy, they are sick. A lazy person has motivation – he is trying to get himself out of some work. The ill person doesn’t have any motivation, his brain just doesn’t work properly. Would you accuse a person with a brain tumor of being lazy?

Me

Gradually Papa stopped taking any care of himself. He stopped showering, his teeth started falling out. He ate a lot, hardly moved and grew obese. I was starting to feel ashamed of him. In the early years I had wishes to use my piggy bank savings to buy him a ticket so he could visit me. Now I didn’t want to invite him anymore. The last time I saw him was in 2010. I really wanted to talk to him. C’mon, tell me what’s happening to you, please, don’t be such a stranger. I suggested we take a walk along the Volga river, papa agreed: “Ok, but first we stop at the bar”. I made him promise it would just be one drink. In the end, he said he won’t leave the bar without a 4th drink. When we left the bar, he was singing songs. I got angry and promised myself not to visit him again. I kept that promise.

Papa died on October 12, 2013. Together with my grandfather they were collecting walnuts from the trees at our summer house. Once upon a time, two walnut trees were planted there: one on the occasion of my sister’s birth and the other on the occasion of my birth. On their way back to the bus stop, my father went ahead and my grandfather stayed behind. Somewhere along the way my father drank some counterfeit vodka. He fell on the road, face down. It was a heart attack. Somebody called the ambulance, but the doctors didn’t come fast enough. Papa was 53 years old.

When I heard about his death I felt nothing. I didn’t want to cry. I just kept imagining people passing my dead father lying on the road and thinking to themselves “Yet another drinks himself to death”. As if he was some worthless alcoholic.

The next day after his death I arrived in Volgograd. I picked a spot for him in the graveyard. On top of a hill with a view on the lake and summer houses. It felt like papa was finally moving to a good place.

In the morgue we were told there was an excess of corpses that weekend. Not enough refrigerated space for everyone. Many corpses lay in the corridor. Papa turned black. We had to bury him with a cloth on his face. During the ceremony I had a thought: what if that’s not him? I took a closer look and recognised his nose. When I was a child, we would rub our noses against each other and we enjoyed noticing they were of the same shape. He was dressed in a ridiculous suit and slippers, his feet tied with a rope. The funeral agent made a speech and called me Galina instead of Polina. I’m sure papa would’ve found that funny.

Originally published in Esquire magazine (Russian edition), October, 2014, link